Disinvestment in Public Sector Enterprises and its Changing Dynamics

Public Sector Enterprises (PSEs) played a pivotal role in transforming India, to its current heights. From Industrial Policy 1956, the public sector underwent large-scale expansion. This expansionary trend was reversed in 1991 with the Industrial Policy of 1991. Yet, PSEs continue to play an important role in Indian economy. This is reflected in growing number of PSEs in India. There were only 5 CPSEs in 1951 but by 1969, the number grew to 84. The number of CPSEs trebled to 260 in FY 2011-12, and increased to 389 in FY 2021-22.

Over the years, as the role and capacity of private enterprises in the economy grew, questions were raised on continued utility of PSEs. Moreover, it was long realized that most of these PSEs have been marred with inefficiency and corruption. Thus, disinvestment gained currency among Indian policymakers.

This note has been divided into four sections. Section 2 provides a brief overview on evolution of disinvestment policy since its inception. This was followed by a section examining challenges to disinvestment in India. Finally, a conclusion has been provided, along with some recommendations.

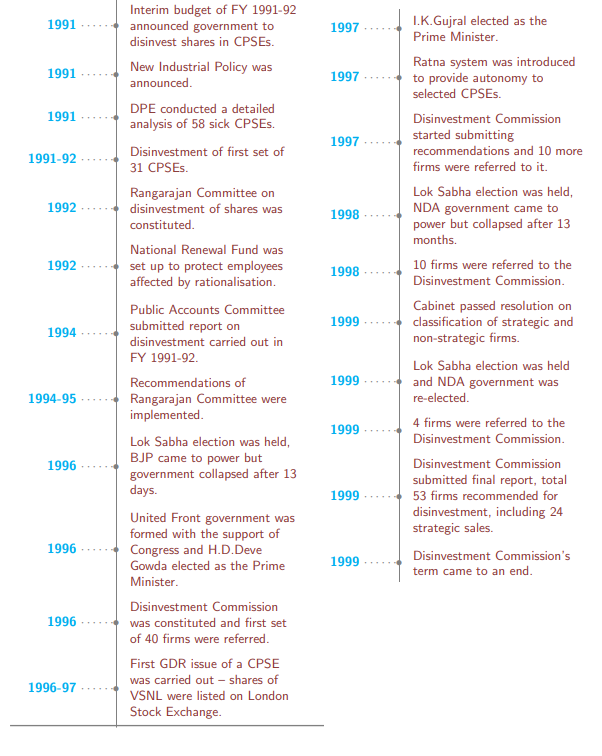

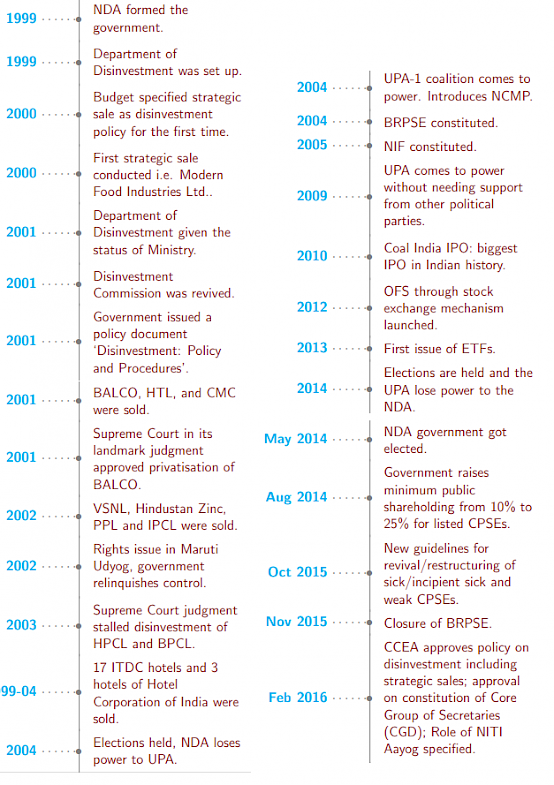

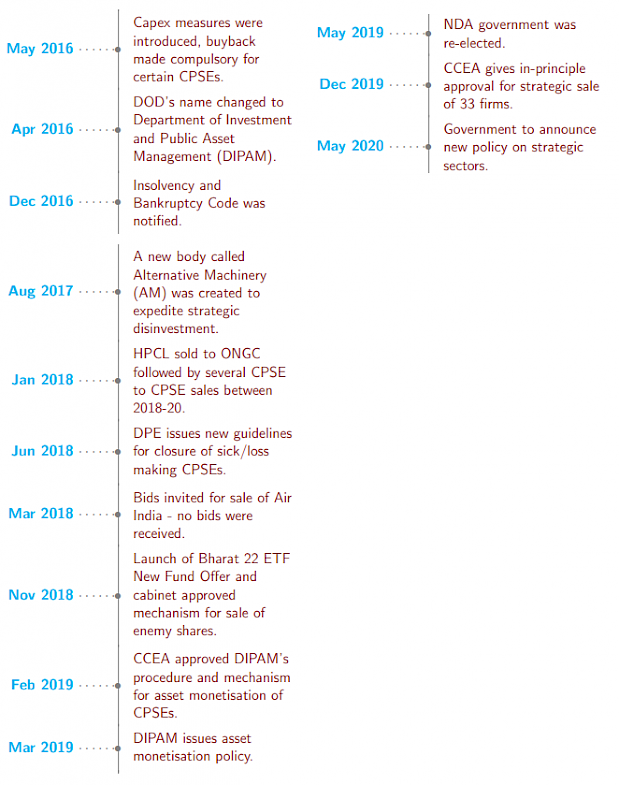

2: Evolution of disinvestment policy in India

Banerjee et al. (2022) divided the historical timeline of disinvestment in India into four phases. The idea of disinvestment in India gained pace in 1990s in the wake of poor performance of CPSEs and balance of payment crisis. During this phase, a wholesale privatization (also called “strategic sales”) was avoided and minority stake, averaging around 8.87 percent in select PSEs, was diluted. It was during phase 2 of disinvestment, between 1999 to 2004, when privatization took place. This phase saw strategic sale of 12 PSEs. The period also oversaw disputes over privatization on issues of job losses, methods of valuation and legal disputes on transactions. As a result, Phase 3, beginning from 2004 oversaw return to a policy of retaining public character of PSEs. During this period, policy was to undertake disinvestment on case by case basis and retain profit making PSEs. Moreover, PSEs were encouraged to tap capital markets. There were no strategic sales taken during this period.

A new impetus to the idea of privatization in 2014. In its first disinvestment policy, announced in 2016, emphasis was laid on efficient management and promoting public ownership. Subsequently, the policy oversaw an evolution, with Department of Disinvestment being renamed as Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM) with the expansion of its mandate to manage government investments along with disinvestment and larger role for NITI Aayog. As per a new government notification on PSEs (2021), the Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs), were divided into Strategic and Non-Strategic Sector. CPSEs in the Strategic Sector/ Non- Strategic Sector will be taken up for privatisation, merger, subsidiarisation with another CPSE or for closure. Only a bare minimum presence of CPSEs in the Strategic Sector is to be maintained. Moreover, new strategies such as asset monetization, expansion of scope of disinvestment to enemy properties and the sale of holdings in SUUTI (a statutory special administration for the management of the restructured Unit Trust of India in 2002) were adopted.

Government of India (2023) noted that disinvestment is seen not only as a tool to shore up government financials, but also as a means for crowding-in private investments by vacating non-strategic sectors of the economy and engaging with the private sector as a partner in the development process. The government’s disinvestment policy has been revived in the last eight years with stake sales and the successful listing of PSEs on the stock market. During FY15 to FY23 (as of 18 January 2023), about Rs 4.07 lakh crore has been realised as proceeds from disinvestment through 154 transactions using various modes/instruments. The privatisation of Air India was particularly significant for re-igniting the privatisation drive.

3: Trends in disinvestment in India

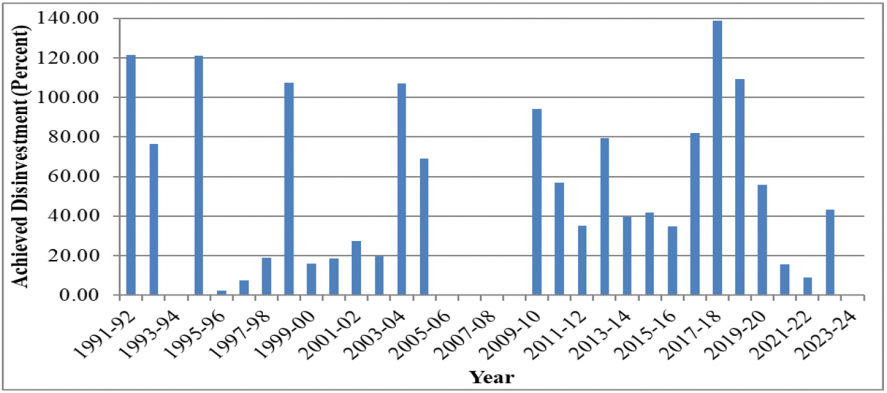

The role of disinvestment in fiscal management has increased over the years. IN FY 2024, government expects to receive Rs 51000 crore from disinvestments. In 2022-23, the government is estimated to meet 77.0 percent of its disinvestment target (Rs 50,000 crore against a target of Rs 65,000 crore). This is a marginal increase of 2.0 percent over the revised estimate of 2022 23 (Graph 1 and Table 1).

Graph 1: Historical data -Achieved Disinvestment as a percentage of Disinvestment Target

Source: http://bsepsu.com/Annual_Table.asp

Table 1. Annual Disinvestment Target vs. Achievement since 1991-92

|

Year |

Target |

Revised Target |

Achieved* |

Achievement |

|

(Rs. crore) |

(Rs. crore) |

(Rs. crore) |

(%) |

|

|

1991-92 |

2,500 |

3,038 |

121.51 |

|

|

1992-93 |

2,500 |

1,913 |

76.50 |

|

|

1993-94 |

3,500 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

1994-95 |

4,000 |

4,843 |

121.08 |

|

|

1995-96 |

7,000 |

168 |

2.41 |

|

|

1996-97 |

5,000 |

380 |

7.59 |

|

|

1997-98 |

4,800 |

910 |

18.96 |

|

|

1998-99 |

5,000 |

5,371 |

107.42 |

|

|

1999-00 |

10,000 |

1,585 |

15.85 |

|

|

2000-01 |

10,000 |

1,871 |

18.71 |

|

|

2001-02 |

12,000 |

3,268 |

27.24 |

|

|

2002-03 |

12,000 |

2,348 |

19.57 |

|

|

2003-04 |

14,500 |

15,547 |

107.22 |

|

|

2004-05 |

4,000 |

2,765 |

69.12 |

|

|

2005-06 |

0 |

1,570 |

0.00 |

|

|

2006-07 |

0 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

2007-08 |

0 |

4,181 |

0.00 |

|

|

2008-09 |

0 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

2009-10 |

25,000 |

23,553 |

94.21 |

|

|

2010-11 |

40,000 |

22,763 |

56.91 |

|

|

2011-12 |

40,000 |

14,035 |

35.09 |

|

|

2012-13 |

30,000 |

24,000 |

23,857 |

79.52 |

|

2013-14 |

54,000 |

19,027 |

21,321 |

39.48 |

|

2014-15 |

58,425 |

24,349 |

41.68 |

|

|

2015-16 |

69,500 |

25,312 |

24,058 |

34.62 |

|

2016-17 |

56,500 |

45,500 |

46,378 |

82.09 |

|

2017-18 |

72,500 |

1,00,000 |

1,00,642 |

138.82 |

|

2018-19 |

80,000 |

87,513 |

109.39 |

|

|

2019-20 |

90,000 |

65,000 |

50,294 |

55.88 |

|

2020-21 |

2,10,000 |

32,000 |

32,742 |

15.59 |

|

2021-22 |

1,75,000 |

78,000 |

15,440 |

8.82 |

|

2022-23 |

65,000 |

50,000 |

28,156 |

43.32 |

|

2023-24 |

51,000 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

TOTAL |

12,13,725 |

4,38,839 |

5,64,860 |

47.0 (Average) |

* Excludes Other Receipts of the Government from CPSE Disinvestment as on March, 2023

Source: http://bsepsu.com/Annual_Table.asp

4: Challenges to disinvestment

Much for its role in propelling the economy through crowding in private investment and promoting efficiency, disinvestment is not without its challenges.

One of the major issues is with regard to non-realization of disinvestment targets by the government (Table 1). In the past years, the central government has been able to meet its disinvestment targets only twice. The percentage of realized amounts have been particularly low in the last four years. This is majorly due to lag in planned disinvestment and its realization, or market factors making it less attractive for private sector to make new investments.

Moreover, there are issues concerning the sale of one PSE to another, the proceeds of which are also included in realized receipts from disinvestment. Between FY 2016 to FY 2021, all the transactions where the government sold more than 51 percent of its stake in PSEs, have involved other PSE picking up government’s share. These instances included the sale of HPCL to the state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGCL), which fetched the government Rs 36915 crore.

Another issue is with regard to valuation of public assets for privatization or monetization. This has even led in delay in implementation of New PSE policy. For instance, the launch of the planned special purpose Vehicle (SPV), National Land Monetization Corporation (NLMC) for asset monetization was delayed due to delays in finalizing the value of assets at which they will be transferred to it. Concerns lie not only in fair valuation of these assets by the government, by also, undertaking privation at these prices.

Beyond these, challenges also remain around interests of PSE employees, utilization of proceeds of disinvestments and overcoming legal disputes between the government and the private enterprise buying government’s stake. Moreover, there are criticism surrounding the issue of autonomy in decision making for private sector buyer, even after privatization has taken place. Debates also remain around the sale of profit making PSEs.

5: Conclusion

PSEs must become an engine of growth, rather than a drag on it. The public sector will have to undergo numerous changes from to achieve this feat. Changes will be reflected mainly in the form of disinvestment, partial disinvestment, improving key enterprises, improving corporate governance structure and adding new CPSEs that have high profitability. Ideally it is expected that the government should not own more than 20.0 per cent share of the product market in any of the sectors and these CPSEs should be more sustainable and should not seek dependency on the government. Regarding criticism that there is lack of delegation and external control, which discourages development of decision-making culture, a reform to address these issues and improve the efficiency of the CPSEs is expected to take place in near future. The profitable CPSEs which are non-essential services like tourism, engineering, construction, trading and consumer products can be sold off without compromise with strategic interest or loss of control.

It should be noted that proceeds of disinvestments not only depend on government intent or regulations, but also, several external factors such as interest rates, market sentiments, inflation etc. At this point, global growth outlook, interest and inflation environment, along with the unfolding crisis in the financial sector do present a compelling case to go ahead with aggressive disinvestment. While it may be compelling to meet the budgeted targets, government should note that these targets should not be achieved through sale of public assets below their fair value, at a loss to the taxpayer.

Beyond these, disinvestment policy of government should be based on long term vision of share and role of government in the future economy.

In the light of increasing importance of currency and payment system in an economy, it seems that the role of government in facilitating economy has evolved. Over traditional PSEs, government has emerged as a facilitator of New Economy, like sponsoring new forms of payment platforms like BHIM and UPI.

Annexure 1

Source: Banerjee et al. (2022). https://www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2022/03/WP_373_2022.pdf

Assitance by Ayanendu Sanyal and Priyanshi Goel is acknowledged