The Siliguri Corridor

The Siliguri Corridor has been always been a vexing question for the Indian National Security establishment. Only 22km wide at its narrowest, this piece of land connects the Indian mainland to the North East of the country. The North East, itself has been the face of several Chinese transgressions and one border war in 1962. China has still not foregone its claims over the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh, which it considers to be Southern Tibet. Given China’s stupendous rise over the past two decades and its recent militaristic acquisition of disputed islands in the South China Sea, the Indian security establishment has not ruled out armed conflict with China. Furthermore, the Doklam standoff in 2017, where China tried to alter the status quo on the ground near the Doklam Plateau really highlighted threats to Indian national security. The Doklam Plateau is a small piece of land that pushes out like a dagger into India’s Siliguri corridor and its annexation by China would have posed a serious security risk.

Given this situation, the Siliguri Corridor is India’s Achilles heel. If occupied, China could possibly cut off the entire North East from the rest of India, blocking logistics and supply routes which are critical to defence of the region. At this juncture, it would be prudent to ask how India’s political leadership could let such a glaring geographical anomaly persist at the time of boundary formation and what are the implications of this strategic vulnerability today.

The history of the corridor

Borders

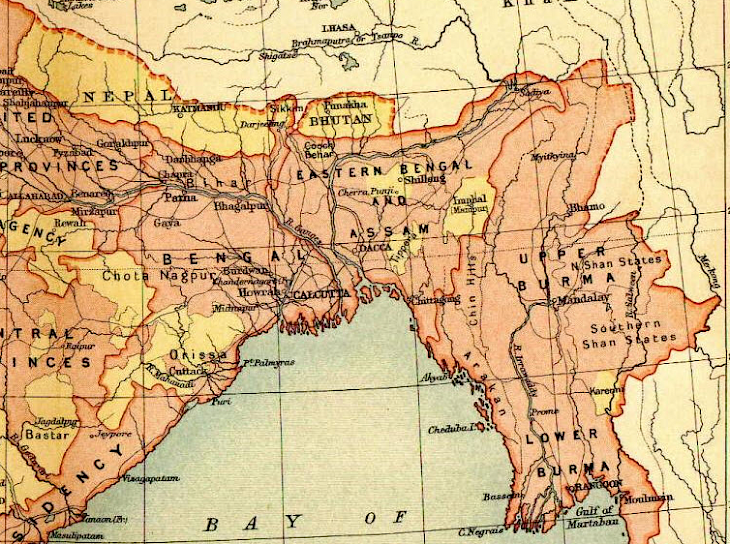

The modern day Siliguri corridor shares its borders with three neighbouring countries- Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. At the time of Partition in South Asia, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British civil servant, was commissioned to draw up the boundaries for India and Pakistan. However, during British India, the region that is now the Siliguri Corridor shared its boundaries with completely different sovereign nations/kingdoms- Nepal Bhutan, Sikkim and Tibet. Its boundaries at the time were quite different from what it is now. In British India, Bengal was one of the largest provinces of the East India Company and encompassed modern day West Bengal, Bangladesh and parts of Assam. This changed however, in 1912 when the capital of British India was shifted from Kolkata to New Delhi and both West Bengal and modern day Bangladesh became part of the Bengal province and Assam was made into separate province altogether. The region’s northern borders were however the outcome of several wars with regional kingdoms.

Although the three northern kingdoms of Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan used to fight against each other frequently and within their own kingdoms, they all eventually fought the British. The first war that the British engaged in was the Anglo-Gurkha War from 1814-1816. This war saw the Gurkha Empire which occupied several tracts of lands from the Kingdom of Sikkim, repatriate these lands to Sikkim after the British intervened on Sikkim’s behalf. In the Treaty of Sugali (1816) Nepal was forced to cede much territory including what is now the Darjeeling District of West Bengal. Later in 1853, the British themselves seized the Darjeeling district after a brief military skirmish with the Kingdom of Sikkim. In 1865, when Britain went to war with Bhutan, the war lasted only five months. In the wake of Bhutan’s defeat, Britain took, under the Treaty Sinchula, the ‘Doars region’ a part of which was, what is now, the Jalpiaguri district in West Bengal. Later, all these kingdoms revised their treaties with the British, but the boundaries remained relatively the same. These two districts in the northern part of West Bengal, Darjeeling and Jalpiaguri form the current upper boundaries of the Siliguri Corridor.

The final treaty that merits attention is the 1890 Anglo-Chinese convention. This treaty was signed between the British and Qing Dynasty which was in power in China at the time. The treaty looked to transform Tibet into a buffer zone between British India and the Russian Empire. This Treaty also settled the borders between the Kingdom of Sikkim and Tibet. The different interpretations of this treaty on the demarcated boundaries led to the Doklam standoff in 2017 between India and China. Later, three party talks were held between the British, The Tibetans (who had declared independence from the Chinese Empire after the fall of the Qing Dynasty) and the Republic of China. The Treaty of Lhasa as it was later called was meant to ratify borders between Tibet, China and British India. Although this treaty didn’t directly deal with the borders of Bhutan and Tibet, the “watershed principle” to demarcate the borders was the basis of this Treaty, and is also the basis of 1890 Treaty to demarcate the Doklam Plateau.

Figure 1: Map of the Siliguri area and neighbouring kingdoms in 1865- present day Bhutan Nepal India Bangladesh border

Bangladesh forms the southern border of the corridor. Bangladesh was formed from the erstwhile East Pakistan, whose boundaries were drawn by the Boundary Commission led by Sir Cyril Radcliffe. In the run-up to Partition, the Bengal region (West Bengal and Bangladesh) existed as the Bengal Presidency. The Bengal Presidency had its boundaries altered multiple times even before Independence, the most consequential of which was in 1905, when it was partitioned on religious lines. Once the Muslim League began its demand for a separate state of Muslims and didn’t want to get subsumed into a Hindu majority India, these calls reverberated in the Bengal Presidency as well. As in 1905, the Bengal Presidency was again divided purely on religious lines. The most consequential districts in the Siliguri corridor, Darjeeling and Jalpiaguri, were to stay with India as the population was majority Hindu. The districts on the opposite side of the border in Bangladesh are Thakurgaon, Panchagarh and Dinajpur. All these districts were initially part of a single Dinajpur district which was under the Bengal Presidency during British Colonial Rule. During partition, the Dinajpuri district was itself divided on religious lines to form the West Dinajpur district in India and Dinajpur district in East Pakistan (which is now the Thakurgaon, Panchagarh and Dinajpur in present day Bangladesh).

Strategic Developments Post Independence

During the time of India’s Independence and Partition, the Executive Council of the Congress Party and the Muslim League was in close consultation with the Boundary Commission and the Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten on the division of borders between India and Pakistan. While the boundary commission divided India and Pakistan on religious lines (even in East Pakistan as elucidated above), it was decided that Sikkim and Bhutan weren’t Himalayan Kingdoms and not states of India. Their boundaries could be negotiated separately.

At the time of boundary negotiations, the key strategic developments were yet to occur and hence at the time no conceivable threat could have been perceived to the Siliguri corridor. In 1947, China was still in a state of civil war, the warring factions being the Republic of China and Communist Party of China. The Communist Party of China came to power only 1949. But at the time, Tibet was still an independent country. In 1950, Chinese forces occupied Tibet, although they maintained that it was to remain an autonomous region. But as relations proceeded, India and China developed a thaw in relations when India promptly recognised Tibet as a part of China and Prime Minister Nehru and Chinese Premier Zhao Enli signed the Panchsheel Agreement which dictated the five points of peaceful coexistence. India had already proceeded to sign agreements of suzerainty with Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim by 1950. It is not clear how much the threat to the Siliguri corridor pre-occupied the minds of the India’s policy makers in the early to late 1950s.

However, some in the government realised there existed such a threat even in 1950. Claude Arpi quotes from a classified communication from Hariswhar Dayal, the then Indian Political Officer in Sikkim to the MEA on 21 November Doklam and the Indo-China Boundary 9 1950, one month after PLA invaded Tibet and occupied the town of Chambdo:

“An attack on Sikkim or Bhutan would call for defensive military operations by the Government of India. In such a situation, occupation of the Chumbi Valley might be a vital factor in defence. In former times it formed part of the territories of the rulers of Sikkim from whom it was wrested by the Tibetans by force. It is now a thin wedge between Sikkim and Bhutan and through it lies important routes to both these territories. Control of this region means control of both Jelep La and Nathu La routes between Sikkim and Tibet as well as of the easiest routes into Western Bhutan both from our side and from Tibetan side. It is a trough with high mountains to both east and west and thus offers good defensive possibilities. I would therefore suggest that possibility of occupying the Chumbi Valley be included in any defensive military plans though this step would NOT of course be taken unless we became involved in military operations in defence of our borders.”

But shortly after the India-China War of 1962, both countries have had disputes over the Chumbi valley in the region. India and China fought a bloody skirmish at the India-China-Sikkim-Bhutan junction in 1967 again due to the misperceptions of the border junction. It is evident that this region was recognised as a strategic vulnerability due to heavy presence of both Indian and Chinese troops in quite close proximity to each other. India’s position viz-a-viz the defence of the Siliguri corridor improved significantly after Sikkim joined India as its 22nd state. However, the border dispute in the region festered and China continued to send herders, grazers and regular army patrols into Chumbi valley.

Figure 2: Borders of Eastern South Asian region after partition

There had been protests of Chinese incursions into the disputed territory in Doklam even in the 1960s. In 1979, after Thimphu and New Delhi protested against regular intrusions by Tibetan herders into Bhutan, Beijing ignored the Indian protest, responding to the Bhutanese complain only. Since then China has looked to engage Bhutan bilaterally to solve the dispute between the two countries. Since its first engagement with Bhutan in 1981, China and Bhutan have held several rounds of talks on their border dispute but to no avail.

In 2003, India and China came to an agreement whereby China agreed to Sikkim’s annexation to India and gave up all claims to the state and India recognised China’s sovereignty over Tibet. While this significantly reduced the escalation in the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction region, China’s attempts to seize the de-facto control over the region continued. It all culminated in the Doklam Standoff between India and China in June-August 2017. After a mutually agreed disengagement, tensions have reduced. But a threat to the Siliguri corridor still remained as China has continued its overt road construction activities on its side of the border. This could allow China to rapidly mobilise and deploy troops thereby threatening to Siliguri Corridor. Furthermore, the deployment of artillery, missiles or anti-aircraft weaponry could jeopardise India’s efforts to resupply the region in the time of war, especially considering that there is only a single railway line through the region to the North East of India.

Figure 3: India-China-Bhutan trijunction at Doklam; site of 2017 India-China military standoff

Figure 4: The Siliguri Corridor

Strategic Relevance

Terrain Analysis

The districts of the state of West Bengal which encompass the Siliguri Corridor are – Darjeeling, Jalpiaguri, Kalimpong and Uttar Dinapuri. The Uttar Dinapuri district is where the corridor is narrowest with the width of the corridor being a mere 20km. The district is bordered by Nepal to its North and Bangladesh to its South. However, any military threat should one arise, will emerge first to the other three districts which border the disputed tri-junction area between India, Bhutan and China. The border along the Sikkim-China border and the West-Bengal Bhutan border is divided by sharp Himalayan mountain ranges. However, the Jampheri ridge is the point from where the mountains of the Himalayas begin to descend into the plains and foothills in Darjeeling and Jalpiaguri. The districts also have a large forest cover and many small rivers that eventually drain into the Ganga.

Strategic Vulnerability

Control of Mount Gipmochi (which is China’s claim point as the India-China-Bhutan trijunction) would give the Chinese a strategic vantage right into the Silliguri Corridor. It is unlikely that the Royal Bhutanese Army stationed on the Jhampheri ridge would be able to offer much resistance. The distance between the claim points of Bhutan and China is nearly 5-6km apart. Such a distance could give the Chinese immense advantages in artillery fire on the narrow corridor. It is important to remember that currently as things stand, only a single railway line passes through the corridor and is the link between mainland India and its north eastern states.

In general as well, due to its width, the corridor is always at risk of being subjected to conventional military strikes by the Chinese air-force and Special Forces operations to subvert logistical supply through the corridor. Apart from this there also exists a hybrid threat to the corridor. Currently, several ethnic groups in the region have been calling for autonomous administrative regions of Bodoland and Gorkhland in the area of the corridor. Furthermore, some insurgent groups such as the United Liberation Front of Assam and Maoists are known to operate in the area or close proximity to the area.

The Way Forward

The Siliguri corridor, although a relic from the times of Partition, is still a constant irritant in India’s dealings with China. For India, it is an inescapable fact that the need to defend this corridor will have a huge bearing in the minds of the military planners in any military conflict with China. Given its insurmountable strategic relevance, India is likely to devote a large number men and resources to defend this piece of real estate. This would entail a diversion of resources from the main battle front and could even possibly dilute India’s deterrent posture on the second front with Pakistan. Hence it is critical for India to think outside the box to find avenues to circumvent this vulnerability.

-

The first option for India is to enter into a treaty with Bangladesh permitting the transit of military equipment during times of conflict. This would add a layer of strategic depth in the region and alleviate (in some measure) concerns of the possibility of severance of the North East with the mainland. The treaty can cover all modes of transport like road, rail and air for the movement of freight and personnel. The Bhutan-Bangladesh-India-Nepal economic corridor or BBIN was an attempt to allow for free movement of goods and traffic within the region. However this proposal got shot down in November 2016 when the Upper house of the Bhutanese Parliament repealed legislation that would facilitate the corridor. However, Indian officials still contend that they will be able to salvage the deal. Although this was a setback the Bhutan Government of the time had called on the remaining countries to proceed with the agreement. Regardless of the multi-lateral approach, India’s relations with Bangladesh have been seeing a positive trend for the past decade. India and Bangladesh have already mooted a proposal to facilitate transit between India’s landlocked north east and Prime Ministers of both countries have issued joint statements in this regard in 2010 and 2016. Currently also, there is a joint working group which is examining the possibility of connecting Mahendraganj in Meghalaya to Hili Land Port in West Bengal through Goraghat, Palashbari and Gaibandha in Bangladesh. This distance is only 100km and road, rail and air transport modes are under consideration. Officials from both countries are concurrently working on the development of an inland water way connecting Haldia Port in West Bengal to the Brahmaputra in Assam through Bangladesh. The defence cooperation has also been increasing and two agreements were signed in this regard in April 2017. India has also been extending lines of credit and pushing from investment from multilateral organisation for infrastructure development in Bangladesh (and the larger region). If India is able to develop such an elevated corridor through Bangladesh, it will go a long way in improving India’s National Security.

-

The second option for India to circumvent the challenges raised by partition is to make alternate transport arrangements within the country itself. The development of a multi-modal transport corridor through Siliguri itself can be undertaken by India. A part of this initiative can look to build underground tunnels which is less likely to be susceptible to air and artillery attack in a time of a military conflict. Underground tunnels through the narrow vulnerable stretch in the Siliguri corridor, although costly, can give India a little more room to take harder line militarily when required.

Through some of these measures India can look to overcome the constraints imposed by geography and improve its position vis a vis China.

Col Mohinder Pal Singh, PhD is a defence and geopolitical analyst. He is Senior Fellow CLAWS. Views expressed are personal.